Defining Civility

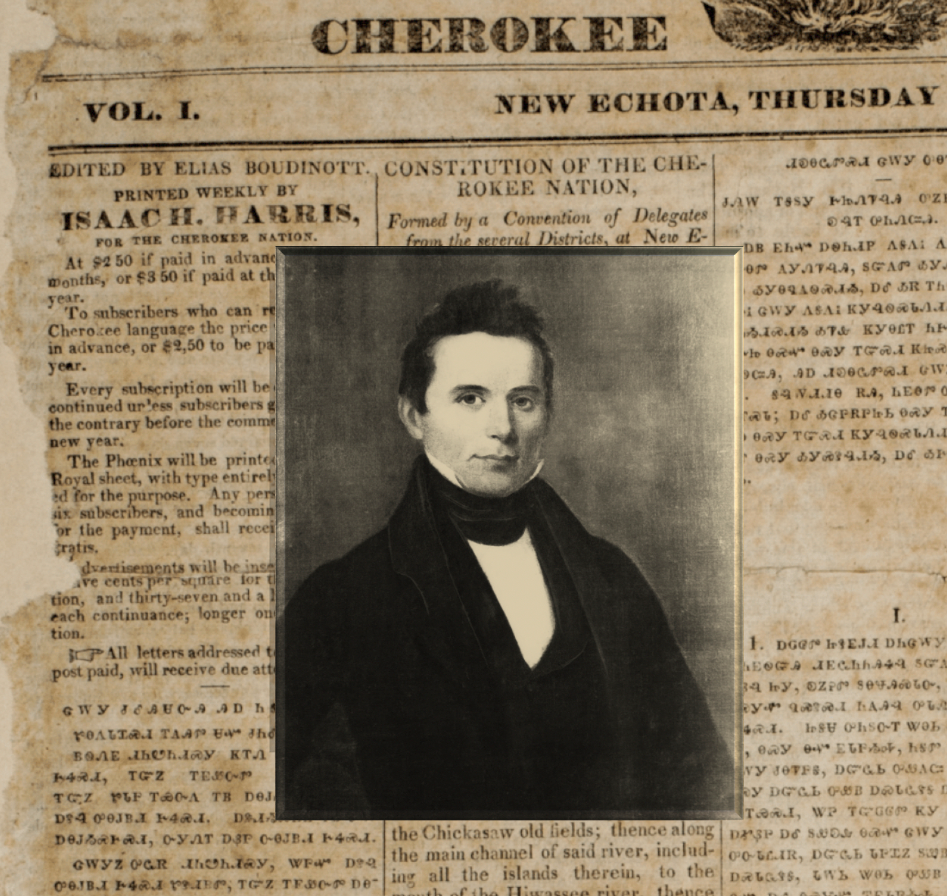

A term as common as the word “civilization” can have many meanings and many connotations depending on the context in which it is used. Generally used to represent what the modern era calls “Western” civilization as a descendant of European colonialism and hegemony, it brings with it a condescending view of the so-called uncivilized, or “savage” people of the world. If civilization does equal the European, colonial, and often Christian, Western civilization, then if an “uncivilized” people adopt this definition of civilization for themselves, they too would be civilized and therefore equal and independent. According to his writings and speeches Elias Boudinot rhetoric supported this logic, born into the Cherokee Nation and educated in a New England mission school, who returned to establish the first Native American newspaper with the explicit aim to benefit the Cherokee Nation and prove its desire for, and accomplishments, of “civilization.”1 Through his public speeches and the publication of the Cherokee Phoenix, Elias Boudinot helped shape an identity of Cherokee people and the concept of “civilization” as it was understood both by Cherokees and white Americans, specifically southerners. Boudinot and other Cherokees understood civilization as a means to sovereignty and land retention, while white southerners strived to use their own understanding of civilization, fueled by white supremacy, for social and political hegemony and justification of acculturation and eventual Removal.

From a white American perspective, civilization equals sovereignty; the United States, a civilized, sovereign nation, declared independence from England and with official treaties between two civilized nations became legally independent with one no longer subject to the other’s rule. Because both the established colonies and England were equal in their status of civilization and race, one having derived from the other, as a result of the Revolutionary War, there is no dispute in the agreement to be separate and sovereign. A complication arose when Elias Boudinot’s own writing seemed to support the perceived superiority of Western civilization and adopted its traditions. He had a strong desire to foster and encourage the adaptation of this manner of civilization within the Cherokee Nation and prove the capability of Indians to be civilized and equal to their white neighbors, and therefore also sovereign and independent in their own right.2 If Cherokees, and other Indians, were equally capable of civilization, within the same terms of Western civilization, it would follow, within that same doctrine, that to deny legitimate sovereignty to the Cherokee Nation would be immoral.

The southeastern corner of the new United States in the early 19th century was emerging with a conflict of identities. The plantation economy, supported by the enslavement of Africans and the culture of cotton, encouraged the disparity between rich and poor, white and black, while establishing a southern prosperity and promise of upward mobility for the white southern Americans enjoying prosperity in their new nation. This new southern identity left out or overpowered the conflicting struggles in the South of both enslaved black people and Indians surviving in the region within what came to be known as the “Five Civilized Tribes” (Creek, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Cherokee, and Seminole). In 1825, the Cherokee Nation established its new capitol at New Echota (near present day Calhoun, GA).3 The name “New Echota” means the “place where we will strike the new fire” in Cherokee. The town was built and designed in the colonial style, adopting European architecture, economics, and style into Cherokee tradition. Along with the national debate regarding the removal of Indians west of the Mississippi River, New Echota emerged within the climate of state nullification in the South, in which some southern states were attempting to nullify federal law that they deemed unconstitutional. Cherokee leaders in New Echota were establishing their own hybrid culture and different stances on these issues. Elias Boudinot was among these leaders; to be civilized and also be Indian, he used both his background of a New England education and his Cherokee heritage to shape the ensuing debate among Cherokees and with their ever-encroaching white neighbors.

Early Life

In 1817, at the age of thirteen, Elias Boudinot was invited to attend the Foreign Mission School in Cornwall, Connecticut, by Elias Cornelius. Boudinot, born as Buck Waite, took his benefactor’s name upon his arrival at the school.4 During his time at the school he gained an education based in Anglo-American tradition, including Christian theology and European philosophy. The main objective of these schools was to evangelize members of Native communities, to instill the importance of agriculture, and to prepare the students to bring education and Christianity back to their people.5 Boudinot thrived in this environment; becoming one of the top students in the school. He often wrote to local religious periodicals publicly showing his gratitude to the benefactors of the school for his opportunity to be educated and be part of those “who are willing to be employed in the work of the Lord.”6 Boudinot not only embraced the benefits of his formal education academically; he also remembered his community of birth. In a letter to the Religious Intelligencer as a teenager he wrote, “I feel sometimes an ardent desire to return to my countrymen and to teach them the way of salvation.”7

Through the elevated scholarship exhibited in his public letters, he caught the attention of Harriet Gold, daughter of one of the school’s benefactors, Benjamin Gold.8 When Boudinot left the school in 1822 due to health problems, he and Harriet continued their written correspondence until 1825, when they announced their engagement.9 In 1824, during their time apart, Boudinot’s cousin, John Ridge, had married Sarah Northrop, another daughter of one of the school’s benefactors, stirring up the controversy of interracial marriage. The Boudinot-Gold engagement inspired a lengthy debate within the Gold family.10 Not only was it a controversial issue of miscegenation between an Indian man and a white woman because of Boudinot’s Cherokee heritage, but also an issue of the sectional divide between the North and the South, because he was also not a Northerner. As tensions were rising between the North and the South in the antebellum period, questions of loyalty and identity were emerging on both sides. Because of his education and extended stay in New England, Boudinot felt a certain amount of inclusion into that white Northern culture, but he would still always be Indian. Herman Vaill, an instructor at the school and brother-in-law to Harriet, highlighted his own flawed logic in a letter to Harriet in the summer of 1825; he wrote, “There is a wide difference between going, because we love the cause of Christ, & have a single eye to his glory; &, going because we love another object; & have a selfish inducement.”11 He found it acceptable to live among Indians if the purpose is to bring them the Word of God, but only in the paternalistic sense, not for personal desire. Because non-whites, no matter their achievements of civilizations, were still othered for their race and therefore not deserving of equality with white people, it was only acceptable for them to be separate and subordinate. Boudinot’s own race consciousness was heightened by this debate among her family members, leading him to eventually become critical of the hypocrisy of the Anglo-American, Christian style of civilization which he had strived so hard to emulate and promote.12 This internal identity crisis of existing between two worlds but never being fully part of either began with his engagement to Harriet Gold, and would follow him until the end of his life.

Christianity

As Boudinot struggled with his personal identity in the context of both white and Cherokee society, he made a great effort to Christianize his fellow Cherokees and to bring the mainstream American way of life to his own community in New Echota. In an attempt to reconcile society’s conflicting ideals of being Indian and civilized, he hoped to prove to whites and Indians alike that these were not mutually exclusive. After he and Harriet Gold married, they established themselves in New Echota, building a colonial style home in close proximity to the missionary Samuel Worcester’s home.13 He began his work to create a bilingual newspaper and promote what he understood, according to Theda Purdue, as “civilization programs…an effort many believed would result in retention of their land.”14 Boudinot argued that the invention of the Cherokee syllabary in 1821 by Sequoyah, an man who could only speak Cherokee himself, was a monumental achievement for the Cherokee Nation; as one of the first written language invented by Native Americans in North America, it pushed the conversation concerning the civilization of Indians and its potential.15 Translation of the New Testament into Cherokee and the reproduction of hymns and stories like “Poor Sarah, or the Indian Woman,” he claimed provided positive evidence of their efforts to be civilized and Christian.16

Elias Boudinot set out to prove to white residents surrounding his nation, and to the government of the United States, that Cherokees, and Indians in general, could become civilized according to the terms of Christian Anglo-Americans, especially with their help. In 1826, to raise funds for a printing press to establish the first bilingual Native American newspaper and other religious and educational texts, Boudinot traveled to northern cities to make the case that “with the assistance of our white brethren” Cherokees could become fully civilized. In his speech in Philadelphia he said, “There are, with regard to the Cherokees and other tribes, two alternatives; they must either become civilized and happy, or sharing the fate of many kindred nations, become extinct.” He argued that the improvement of Cherokees had been exhibited in three distinct examples: the “invention of letters,” the “translation of the New Testament into Cherokee,” and the “organization of a Government.” Citing Sequoyah’s syllabary and the Cherokee constitution explicitly modelled after the US constitution, he did his best to present Cherokees as people not only capable of being civilized, but already making progress. With the help of whites outside the nation and outside the South, he believed that Cherokees could raise their own society to one that could be equal to the United States; he took great care to not appear threatening by presented himself and his people as subordinate to whites and in need of their generous support.17

Christianity’s role as a requirement for civilization was perhaps as important as the written language and the newly established constitution and government at New Echota, for religion was the moral and personal acceptance of civilized life. The United States had been founded in Christianity and the two identities of civilized and Christian had been greatly intertwined; in the same way, “savagery” and godlessness were perceived as one and the same by the Anglo elite. Boudinot emphasized his Christianity along other Cherokee leaders and called upon other Christians to not only be sympathetic to his cause, but to be called by the same God to support them. Christianity and religious assimilation throughout history in the US and worldwide has often been one of the first methods employed to establish domination, however even voluntary, or in the case of Boudinot, enthusiastic participation, it would not sway the overwhelming white supremacy at the root of systematic oppression.

The Cherokee Phoenix

In his “Address to the Whites” and throughout his editorials in the Cherokee Phoenix, he emphasized that the progress made by the Cherokee Nation not only benefited Cherokees, but also served as evidence that all Indians could be civilized; he expressed that the future of Indians relied on the success of Cherokees.18 In “Prospectus: For the publishing at New Echota, in the Cherokee Nation, A Weekly Newspaper to be Called the Cherokee Phoenix,” Boudinot said that the paper would be specifically for the benefit of Cherokees, adding, “There are many true friends to the Indians in different parts of the Union, who will rejoice to see this feeble effort of the Cherokees, to rise from their ashes, like the fabled PHOENIX.”19

The Cherokee Phoenix had dual missions; being bilingual and distributed both within the Cherokee Nation and outside, especially in New England where Boudinot had connections through his wife and his time spent there, it aimed to bring information to Cherokees and also inform whites of the progress and sophistication of their nation.20 The first three issues of the Cherokee Phoenix printed the Cherokee Nation Constitution in both English and Cherokee.21 Other examples of poetry, morality, and ethics were printed in the paper displaying the civilized culture of the nation to the world while also making that culture accessible to Cherokees and other Native Americans. A year later, Boudinot decided to amend the name of the paper to the Cherokee Phoenix and Indians’ Advocate to include the larger population of Indians outside the Cherokee Nation with the goal of lifting all the “uncivilized” peoples of the continent up with the Cherokees as equals to whites.22

Boudinot frequently wrote editorials containing that entangled current events and the political debates of the day. The Phoenix published debates from congress on the issue of Removal as well as letters from citizens and articles from other publications, often accompanied by Boudinot’s responses.23 He was always careful to present Cherokee affairs and culture in an admirable civilized manner in an effort to weaken the argument of white supremacy as justification for Removal. On several occasions, he recounted specific examples of how the enlightened way of living in a civilized manner has come to replace the traditional Cherokee customs, such as agricultural advancements and monogamous marriages.24

While careful not to supply any political ammunition to his opposition, Boudinot developed a clever, but almost sarcastic style that was satirical in the way that it jabbed at the cultural consensus of white supremacy. William Apess was a contemporary Indian writer and orator who used a similar style of holding whites up to their own standard of civilized Christians.25 Though no direct correspondence between the two exists, it is likely that Boudinot was aware of Apes and his writings on Indian affairs. Apes applied the ideology of state nullification to Indian sovereignty in Massachusetts, and Boudinot used similar tactics to use the established laws under the US government which were not being enforced by its own leadership to the benefit of whites.26 Boudinot repeatedly wrote about instances when the laws that protected the sovereignty of the Cherokee Nation and its land were not enforced, such as the lack of regulation on gold speculators moving into Cherokee land at the encouragement of appraisers and with no legal consequence. He is explicit when he describes the transgression, “This is what we call force—this is what we call oppression, systematic oppression.”27 Usually with a reserved tone, both Boudinot and Apes, along with others, writing on injustice at the time, managed to sneak in insults and intellectual blows to those who thought of themselves as a “civilized elite.”

In one editorial, published in response to a letter sent to the Cherokee Phoenix, Boudinot first introduced the published letters with an extra hint of sardonic commentary. He wrote, “We have headed this article civilized correspondence, because the letters we propose to publish are written by those who call themselves civilized and hold the Indians in utter contempt for their ignorance and degraded condition.” The original letter, full of misspellings and vulgar language, is essentially an attack against Boudinot and the paper; cheap insults and idle threats were easy targets for Boudinot to highlight for his audience, and he ultimately begged the question of who was truly more civilized.28 He consistently probed those who claimed adhere to the civilized ideals of the United States and Georgia to be a better example to Cherokees so that they may also improve and work towards becoming more civilized themselves. The discrepancies of violence committed against Cherokees by white southerners were evidence only of the faults of individuals and Boudinot calls on their own government (the United States) to deliver justice fairly. Unfortunately, more often than not, his requests were ignored, and the Georgia government did very little to prevent the encroachment of speculators and their violent behaviors.

GOLD!

When gold was first discovered in Cherokee territory in the 1820s, miners and speculators flocked to the region hoping to get rich. Though it was unlawful for white settlers to occupy land in Cherokee territory, the law was largely ignored and furthered the debate over Removal and secession of the land.29 In 1832 and 1833, coinciding with the US Supreme Court case, Worcester v. Georgia, in which Chief Justice John Marshall ruled in favor of the sovereignty of the Cherokee Nation, land lotteries began to distribute away plots of land to white Georgia citizens.30 Even before the land lottery began, Elias Boudinot addressed the issue of what he called “intruders” or whites illegally occupying Cherokee land; he wrote, “The intruders who to say the least have acted more like savages towards the Cherokees, than the Cherokees towards them, are still permitted to continue in their unlawful proceedings.”31 In subsequent issues, he continued to report on these intruders, including the murder of a Cherokee man by a white settler; he called on the accountability of the Georgia and Federal government to enforce their own laws regarding the sovereign land belonging to the Cherokee Nation.32

In no uncertain terms, Boudinot pointed out the US and Georgia government turning a blind eye to the violence against Cherokees to delegitimize to their own standard of civilization in contrast to savageness they ascribed to Cherokees and other Indians. When the civilized status of an individual is more closely associated with the color of one’s skin than the nature of one’s actions, it breaks down the logic of paternalism as a motivation for assimilation. If anyone who is not white will be seen by white people as uncivilized solely based on their skin color; the goal of assimilation is a goal of oppression and not one of equality. Throughout his writings, both publicly and privately, Boudinot struggled with the false dichotomy of civilized versus savage, adopting many ideals seen as civilized while retaining his Indian identity. To white Christians in the South during his time, civilized and Indian were essentially mutually exclusive. Despite the logic of Boudinot’s argument, white supremacy remained the driving force against Indians in the South. The gold found in north Georgia only added to the monetary motivation to the aggression against Cherokees rooted in the plantation economy.

Worcester v. Georgia

In 1831, missionary and friend to Elias Boudinot, Samuel Worcester was arrested under the law prohibiting whites from inhabiting Cherokee territory. Worcester was welcomed by Cherokees and had worked alongside Boudinot in his missionary work in New Echota. Though this law was not enforced upon the illegal speculators for gold mining, it was enforced as an effort to diminish Cherokees access to resources, trade, and labor.33 When Worcester was arrested and tried, he took his case all the way to the US Supreme Court to challenge the jurisdiction of Georgia law in the Cherokee Nation. The question of the case was whether or not Georgia had the right to make and enforce laws with the territory of the Cherokee Nation; Worcester v. Georgia challenged the court to decide the legality of Cherokee sovereignty. In Chief Justice John Marshall’s decision in 1832, he stated, “The Cherokee nation, then, is a distinct community occupying its own territory, with boundaries accurately described, in which the laws of Georgia can have no force, and which the citizens of Georgia have no right to enter, but with the assent of the Cherokees themselves, or in conformity with treaties, and with the acts of congress. The whole intercourse between the United States and this nation, is, by our constitution and laws, vested in the government of the United States.”34 The Cherokee Nation had been officially recognized by the US government, and Boudinot reprinted, from the New York Observer, an article explaining for the public the nature of the court’s decision in both Cherokee and English.35

The Supreme Court decision was a victory for the Cherokee Nation on paper; legally the State of Georgia had no jurisdiction in Cherokee territory. However, President Andrew Jackson had no interest in enforcing the ruling. President Jackson is remembered as responding to the decision with the famous words, “Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it.” Whether or not he actual said it exactly in those words is a subject of historical debate, but it does accurately sum up his attitude and his actions following the decision. Jackson refused to secure Cherokee sovereignty and allowed the State of Georgia to continue with efforts of Removal and the land lottery. Worcester was not released for almost a year after the decision was made and only by a pardon from Governor Lumpkin of Georgia; at that point, it was clear to Boudinot, Worcester, and John Ridge that the US government was not going to recognize the Cherokee Nation as sovereign or its people as equal to whites under any circumstances.36

Following the decision and the aftermath of Georgia’s noncompliance with the Court, Boudinot began to show support for a treaty with the US that would reduce the risk of more violence against Cherokees from Georgians and ensure peaceful Removal since he believed Removal was inevitable. Under pressure from Principal Chief John Ross, Boudinot resigned from the Cherokee Phoenix on August 1, 1832, because of his support in signing a treaty.37 In a letter to Governor Lumpkin in 1833, Boudinot was identified among others in favor of a deal that allowed Georgia to pay the Cherokee Nation five million dollars to resettle in Indian Territory.38 Though there is speculation about whether Boudinot chose to support the treaty for personal gain or for the benefit of the nation, there is evidence that he came to the conclusion that Removal was unavoidable and it was in the best interest of his people to make a deal to avoid further conflict and violence. Because of his ideals for Cherokee advancement that he expressed during his time as editor, the latter seems more likely. Theda Perdue wrote that “he took the course of a true patriot” implying that he believed that the future of the Cherokee Nation and the ideals of civilized Indians was dependent on their survival and refusal to make a deal may lead them all to death.39

Treaty of New Echota

The Treaty of New Echota stated “that a sum not exceeding five millions of dollars be paid to the Cherokee Indians for all their lands and possessions east of the Mississippi river.”40 A petition was sent to congress signed by 15,000 Cherokees urging the repeal of the unauthorized treaty, as none of the signers had legal authority within the Cherokee Nation to represent the people, but were unsuccessful (the petition was never read before congress).41 Even though the Treaty was not recognized by Principal Chief John Ross or the majority of Cherokees, in 1838 troops were sent in to remove people from the land and forced them to walk to Indian Territory in what is remembered as the “Trail of Tears.”42

Along with other signers of the treaty, Boudinot moved west before the majority of Cherokees were forced to Remove. On June 22, 1839, in Indian Territory (present day Oklahoma), he was attacked and killed by Cherokees opposing the treaty. According to the Cherokee constitution Boudinot had committed treason, a capital offense, and some individuals took it into their own hands to carry out his sentence; those who had stayed behind and were forced to walk and watch their loved ones die along the way felt a sense of justice for the dead in taking his life. Boudinot knew of the risk to his life with his decision but was compelled by his convictions to do what he thought was best for the future of the Cherokee Nation.43

Elias Boudinot and Cherokee Removal was just one of many examples of how paternalism in the US, especially in the South, has been used as a guise for white supremacy. With the professed intention of civilizing Indians for their own betterment but without allowing them to ever achieve equality with whites, southern Christian identity was called out for the inherent and systematic racism it perpetuates by Boudinot and other outspoken people of color throughout US history. Boudinot brought the debate of race and civilization to the public through his writings in the Cherokee Phoenix, defining his unique perspective and subverting the hegemonic force of white supremacy, even if only for a short time. Unfortunately, this terrible aspect of southern culture, and the resistance to it, does not start or end with Boudinot; the legacy of oppression, disenfranchisement, and violence against people of color in the South continues throughout US history no matter the level of civilized, respectability, or assimilation they achieve. Boudinot is one of many who called this into question and paid a hefty price for his convictions and persistence.

Bibliography

Footnotes

Boudinot, “Cherokee Phoenix,” February 21, 1828–August 1, 1832.↩︎

Vaill, “Herman Vaill to Harriet Gold, June 29, 1825,” June 29, 1825.↩︎

Boudinot, “An Address to the Whites,” May 26, 1826; Walker and Sarbaugh, “The Early History of the Cherokee Syllabary”.↩︎

Boudinot; Boudinot, “Cherokee Phoenix,” February 21, 1828–August 1, 1832.↩︎

Boudinot, “Cherokee Phoenix,” February 21, 1828–August 1, 1832.↩︎

Boudinot, “Cherokee Phoenix,” February 21, 1828–August 1, 1832.↩︎

Boudinot, “Cherokee Phoenix,” February 21, 1828–August 1, 1832.↩︎

Boudinot, “Cherokee Phoenix,” February 21, 1828–August 1, 1832.↩︎

Boudinot, “Cherokee Phoenix,” February 21, 1828–August 1, 1832.↩︎

Boudinot, “Cherokee Phoenix,” February 21, 1828–August 1, 1832.↩︎

Scherer, “‘Now Let Him Enforce It’ Exploring the Myth of Andrew Jackson’s Response to Worcester v. Georgia (1832)”.↩︎

Hardin, “William Hardin to Governor Wilson Lumpkin, April 13, 1833,” April 13, 1833.↩︎

“Cherokee Treaty at New Echota, Georgia, December 29, 1835 (Ratified Indian Treaty)”.↩︎